Project blog: Introductory training at Livability

- Adults

- Disability

- Activities

- Tailored Training (On-site)

We are currently working with the national charity Livability to provide training for their care staff at Livability Horizons, a residential setting for up to 13 young adults with learning disabilities and additional needs in Poole. The Music Therapist leading this project is Kate Fawcett, who takes time here to reflect on this project and some of the considerations relating to working with adults with disabilities and how she and the participating staff are looking to embed music into their care.

Kate writes:

“I’m delighted to be working on my first project for Music as Therapy International, with new partners Livability – a UK disability charity committed to enabling children, young people and adults to live a life that adds up for them.

Three care staff have been identified in advance as being particularly likely to benefit from training. In theory, the plan is to begin by focusing on individual work with staff and the people they support, before looking at possibilities for expanding into group work, but it is immediately apparent on my first visit that one-to-one work will only be possible when staffing numbers allow for this focused approach. In addition, Livability have an explicitly person-centred philosophy which encourages residents to make choices about what they want to do – in between mealtimes and necessary care procedures there is very much a “go with the flow” attitude which means that planning specific sessions at set times doesn’t feel like the best fit here. I’m caught initially between worrying that I ought to be trying to deliver the project in an overtly-structured way and a strong suspicion that working much more flexibly alongside the staff to seize opportunities for music-making as they arise might yield a more valuable, sustainable legacy.

One of the interesting things about the setting is that many of the carers are the same age as the people they are supporting – in their early to mid-twenties. This is a new experience for me – I’ve previously worked in schools, where teachers and teaching assistants are much older than the children, and in care homes, where care staff are usually much younger than residents. Musically, the situation at Livability Horizons feels like a bit of a gift: in an initial conversation about musical preferences, one of the carers states “we like Ed Sheeran”, highlighting in an unforced way the natural overlap in taste here between staff and residents. Similarly, my ears prick up when another carer mentions that he often puts on his own favourite Imagine Dragons tracks when helping the young man he supports to get up and dressed in the morning: “I don’t really know what he would choose, but I like it and he seems to enjoy it too”.

This raises another important point – with the majority of residents here being non-verbal and all but one wheelchair-users (of whom most cannot self-propel), enabling choice is very often a guessing game, in which staff make a leap of faith to introduce an activity and then do their best to read reactions in order to gauge preferences. This feels like a gentle, push-me-pull-you, collaborative way for this discrete community to spend the day alongside each other.

In addition to the core team, there is a body of agency staff – who are hugely varied in age and background. Although in terms of their job they often seem to be reticent, waiting for permanent staff to ask them to carry out a particular care task, I quickly realise that their shyness evaporates around music. One grabs the metallophone beaters eagerly and his eyes light up as he talks about the musical culture in his home village in West Africa – which feels a long way away from his life here as a Masters business student in an English seaside town. An older carer, who is part of the core team, tells me how much he misses the rhythm and energy of his native Cuban music. When I ask tentatively if he plays anything himself, he roars with laughter and says no, but with absolutely no trace of regret – the implicit message is that music is simply a fact of life, woven into the culture and belonging to everyone. I’m thrown back to Christopher Small’s seminal definition of musicking, which encompasses so many different ways of connecting with and through music, and begin to wonder if this might be the touchstone I need to frame the work in this setting.

And so I try to relax into the what-is, rather than imposing structure for my own comfort, and seek to remain alert to every opportunity to integrate music into the warp and weft of the day.

There is a large room currently undergoing transformation into a sensory room. This seems to be the most logical space for conscious musical activity and I find that if I base myself loosely here, people tend to wander in and out, or pass through on wheelchair circuits of the building, increasingly stopping to explore the instruments. I can also actively invite people to come specifically to engage in music. I pile the instruments tidily in a corner when I leave, telling staff that they are very welcome to use them during the week – I am delighted that when I return not only are they scattered all over the place, but also at least one has left the room altogether. Somebody is using them!

Staff and residents tend to congregate in the dining room, adjacent to the kitchen. The television is always on – currently playing wall-to-wall footage from Glastonbury. This is one of the ways in which music is already present here, but arguably not being used to its full connective potential. I sit beside a resident, gently tapping her forearm in time with the pulse of the music and humming along. Another resident hurtles into the room in his wheelchair and points expectantly at the guitar in the corner. I strum and sing to him, with staff clapping along to the beat – he seems delighted and beams at me before whizzing off again.

Later I take the circular chimes over to the one ambulant resident, who is sitting in the corner alone, stimming. Over the course of about fifteen minutes, his curiosity very gradually overcomes his instinctive sensory recoil and he begins increasingly to reach for it and hold on briefly then release the sound. I leave it on the table in front of him and note that ten minutes later, without the pressure of being observed, he is still exploring it.

I strike up a conversation with one of the carers around the convention of the “hello” song and how, in a setting like this, it might feel a bit daft suddenly to start greeting people you have spent the entire day with. We discuss how framing an activity with some kind of introduction is nonetheless useful in terms of understanding and expectations, agreeing that it might also provide a valuable opportunity for residents to recognise and respond to each other. She comments that most of the residents are much more focused on interacting with staff. I mention that on my observation visit, one of the residents was joyfully flapping her hands in a tank of water and inadvertently splashing the resident next to her – who was squealing with laughter and showing signs of anticipating the next dousing. We position the row of chimes between two residents, within reach of both, to see if we might simulate similar splashing musically and create a moment of connection between them. This proves optimistic, as one resident clings to the chimes for dear life and the other curls in on herself – but we both feel the principle has potential!

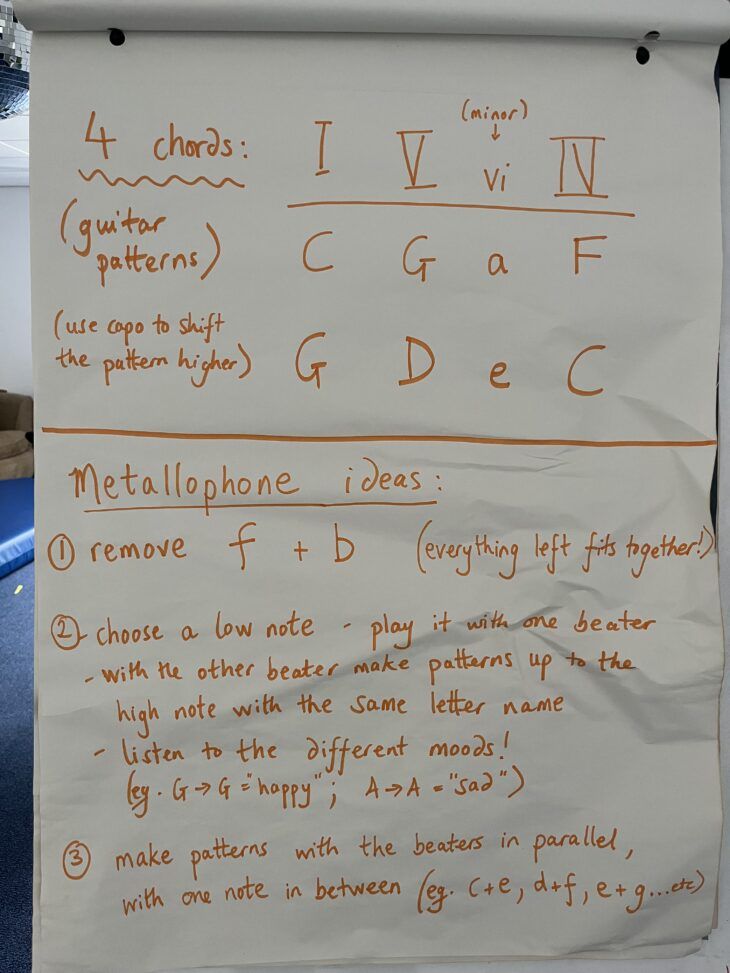

One of the carers expresses a wish to revive and develop his basic guitar skills and I help him to get going with this again. I show him the Four Chords song (Axis of Awesome) to demonstrate how much is possible within even modest parameters (and with a trusty capo – which you clip onto the neck of a guitar to transpose the pitch, meaning you can play more songs with fewer chords!). Over the next few weeks, he grows visibly (and audibly!) in confidence, providing a holding background pattern over which other staff and residents can improvise. I set one of the residents, who has previously shared his Garageband compositions with pride, the challenge of composing some new songs with the carer’s assistance – discussing with them both how to build up a chord pattern and a corresponding set of melodic possibilities.

Another carer is particularly drawn to the sound of the metallophone and I show her how to explore modes by noodling, either a single line or in thirds, over a main note of her choice. She spontaneously muses on how she might use the different moods she can hear to match her sense of what might suit particular residents – whether that is about meeting them where they are or using music to change the feeling in the room. Despite professing herself to be “not really very musical”, she seems to have an instinctive grasp of how music might enable a sense of companionship.

Noticing a flip-chart against the wall, I go on a hunt for markers and set about trying to create some simple play rules based on what we have explored, to prompt people to have a go at playing together during the week. Once I’ve written a few, I ask another carer to come and try them out, to see if they make sense! She is keen, if a little tentative in my presence: “I’ll have to practise!”, she grins. We talk about how she might use some of the patterns I’ve suggested to link with gestures that residents offer – whether or not they are deliberately musical. She says she’s noticed one resident, who often rocks her body backwards and forwards to soothe or stimulate herself, seems to match her movements to tracks with particularly strong beats so we discuss how she might join in too with an instrument, to expand this into something more interactive.

The following week offers a perfect opportunity to explore the needs of two very different residents, back to back, with the same carer. I arrive to find the man who had previously begun to show emergent interest in the circular chimes sitting in the sensory room, just finishing his lunch. Seizing my chance, before he is up and off on his wanderings again, I sit close at hand and start to play the metallophone. This seems to be enough to pique his interest as he stays put when he has had his last mouthful and is clearly paying attention. I try to meet his rocking movements and hand flapping. The carer offers him a maraca and sits down to watch. After a few minutes, which have included what have felt tentatively like moments of togetherness, and some recognition from him of that in the form of facial expression and guttural vocalising, I suggest the carer takes over, which she willingly does – and does a lovely job. A little later, another resident zooms in on his wheelchair – he is characteristically very focused on staff contact, but with a very short attention span. He is expert at making his opinions known, both verbally and gesturally – often pointing and reaching to make himself understood and dismissively rejecting activities with which he has become bored. The carer astutely suggests that he might like to make a video of himself playing the metallophone, to send to his grandad. His eyes light up and we manage a couple of minutes with him playing metallophone and me accompanying on guitar – much to his delight. He’s about to leave, but the quick-thinking carer wonders aloud if he’d like to share his favourite tracks with me, which persuades him to stay. He chooses All Rise, by Blue and, as we listen, I hand out percussion instruments – all three of us play along, instantly transforming what is normally an essentially solitary and passive experience into something joyfully interactive.”

The participating staff and Kate have a few more weeks together to consolidate new skills, to continue putting new ideas into practice, and to think about how the staff can keep music going in the Home after our project ends. Unlike some of our projects, which lead to participating staff running regular music groups, here there is the opportunity to see music laced through the lives of individual young adults, at moments when it could be most meaningful to them. Our thanks to everyone involved for their courage to try new things, their willingness to share their skills and knowledge with each other, and their patient navigation of rotas, competing care demands to make the most of their time together during the project.